Ismael Nery

Untitled

graphite on paper20 x 15 cm

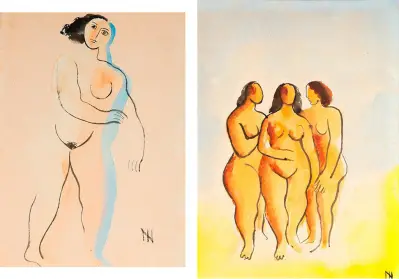

Feminine

watercolor on papersigned lower right

Female Figure - 21 x 16 cm Female figures - 23 x 16 cm

Eve

watercolor on paper1931

22 x 15 cm

Reproduced in the book "Homage to Ismael Nery, an exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of his death", 1983.

Ismael Nery (Belém PA 1900 – Rio de Janeiro RJ 1934)

Ismael Nery was a painter, draftsman, and poet, born in Belém on October 9, 1900. In childhood, he moved to Rio de Janeiro, where his engagement with the arts likely began during his youth. He probably attended the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes – Enba between 1915 and 1916, though he did not adapt to the academic nature of its program. At this stage, he dedicated himself to plaster copies of Greco-Roman sculptures, through which he cultivated a lasting fascination with the human figure—a subject that would dominate his artistic inquiries. At Enba, he studied under Henrique Bernardelli (1858–1936), whose encouragement and praise inspired him to pursue art further.

In 1920, Nery traveled to Paris to study. He spent three months at the Académie Julian, where expressionist influences began to emerge, already carrying the dramatic personal touch that would define his work. While in Europe, he encountered modernism and studied the works of Cubist painters such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Lhote, Fernand Léger, and Jean Metzinger. During his stay, he immersed himself in Europe’s artistic heritage. Beyond the School of Paris, he developed a profound interest in German Expressionism. In Italy, he studied the works of Renaissance masters, becoming an admirer of the period’s painting—especially that of Titian, Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Raphael. He also engaged with the works of modern Italian artists, such as Giorgio de Chirico.

Upon returning to Brazil in 1921, Nery was appointed as a draftsman in the Architecture and Topography Section of the Directorate of National Heritage, part of the Ministry of Finance. There, he met poet Murilo Mendes, one of his greatest advocates, who was instrumental in preserving Nery’s memory and works—often rescuing his friend’s drawings from the trash bin. Mendes became deeply familiar with Nery’s personality and his philosophical system, Essentialism, which was based on the abstraction of time and space and the preservation of elements essential to existence, conceiving the human being in an entirely spiritual sense.

During this period, Nery’s work revealed Cubist influences, the result of his first contact with the School of Paris. It also aligned with the Surrealism of André Breton and Pablo Picasso. Unlike other artists of the First Modernist Generation in Brazil, he did not seek a national identity, but rather embraced universal, internationalist values in keeping with his philosophical and mystical vision.

A year later, he married poet Adalgisa Nery, who became the muse for many of his major paintings. Although he was already working with modern forms, his subject matter distinguished him from the Brazilian Modernism of the 1922 Semana de Arte Moderna. His figures inhabit imaginary settings devoid of recognizable references. He focused primarily on the human figure—idealized and serving a symbolic figuration. At this time, he painted portraits such as Retrato de Murilo Mendes and A Espanhola, marked by a pronounced interplay between light and shadow.

Later, Nery gave his figures a more geometric treatment. Around 1924, he began composing his characters with cylinders and oval shapes. Men and women appeared elongated, structured, and suggestive of idealized forms beyond time and space. To his expressionism, he now added Cubist influence. His home became a gathering place for Rio’s artists and intellectuals, including Mário Pedrosa, Murilo Mendes, Guignard, and Antonio Bento.

Around 1926, he presented his doctrine—Essentialism—to some of these friends. This set of principles, linked to his Christian humanism, synthesized his philosophical reflections. In 1927, Nery traveled to Europe with his wife and mother, where he mingled with Heitor Villa-Lobos and met André Breton, Marc Noll, and Marc Chagall. This journey profoundly influenced his painting, particularly the work of Chagall, whose themes and figures resonated deeply with Nery’s own from that point onward.

Following his encounter with Marc Chagall, the presence of Surrealism in Nery’s work became unmistakable, positioning him as a pioneer of the movement in Brazil. Ironically, it was precisely his avant-garde, internationalist spirit that prevented him from gaining recognition during his lifetime.

From 1930 onward, Nery was diagnosed with tuberculosis, a condition reflected in his work. His figures grew gaunt, with exposed viscera, set against empty backdrops clearly influenced by Italian Metaphysical painting. His subjects now appeared afflicted and wounded, and the theme of death became central.

From then on, the artist worked less, though his production gained greater projection. In 1929, prior to his illness, he held his only solo exhibitions—first in Belém and then in Rio de Janeiro. Though reception was modest, he managed to exhibit at a group show of Brazilian painting in New York and participate in significant salons, such as the Salão Revolucionário in Rio de Janeiro (1931) and the Exposição de Arte Moderna of SPAM in São Paulo (1933).

Despite a brief improvement in 1933, Nery succumbed to tuberculosis on April 6, 1934, passing away in a Franciscan monastery. His work gained recognition only posthumously, following his participation in the Biennials of 1965 and 1969, and retrospectives held in 1966 at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro – MAM/RJ and Petite Galerie.

The social realism of the 1930s and the abstract trends of the 1940s and 1950s left little room for Nery’s spiritual and Catholic figuration. Today, however, he is recognized—alongside Tarsila do Amaral and Di Cavalcanti—as one of the greatest artists of his generation.

Testimonials

"Silence stirred in me an irrepressible urge to run. I darted like an arrow across seas and mountains with incredible ease and without fatigue. Now I find myself seated before a landscape in formation, not yet colored. My mind retraces what I have just traversed, and I marvel at having encountered nothing—until reaching the phosphorescent trail I left behind at the start. The seas now appear as ridiculous sheets of water, scarcely three or four spans deep. The mountains are static clouds, which mankind’s eternal fear will one day transform into granite. Everything is fearfully uninhabited. There are no lions or elephants in Africa’s deserts. The pyramids and the Eiffel Tower do not exist. There is only myself, perceived inversely through an idea I call woman—an ethereal idea hovering above the globe’s surface, incomprehensible, for nothing exists on earth beyond myself.

I traverse space again, though this time with the slow growth of plants, multiplying progressively within my idea to reveal myself to myself. The seas are now deep, and the mountains have solidified. Lions and elephants appear in the deserts of Africa. The pyramids have been built in Egypt, and the Eiffel Tower rises in Paris, in the very year another self of mine was born in Belém do Pará. All has become abundantly populated.

I now find myself seated in a prison cell, gazing calmly through the bars, awaiting judgment for the heinous crime I committed—of using myself, within my mother, woman, daughter, granddaughter, great-granddaughter, daughter-in-law, and sister-in-law. I shall return once more to be my own Judge. Nothing exists beyond myself, save for myself. Silence".

Ismael Nery

Post-Essentialist Poem (1931)

NERY, Ismael. Poemas de Ismael Nery. In: ______. Ismael Nery 100 anos: a poética de um mito. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, 2000. p. 71. [Poems collected by Murilo Mendes and published in Revista A Ordem and Boletim de Ariel, 1935.]

Critiques

"I must say that Ismael Nery’s individual stance openly defied the then-dominant ‘Brazilian’ trend. His painting aligned with the international orientation prevailing at the time—one that still endures in Europe and the most advanced artistic centers worldwide. For this reason, Brazilian themes are almost entirely absent from his art, as they lay outside his aesthetic and visual concerns. He was equally opposed to a painting style of regional, rustic, or folk inclination—whether of Indigenous, African, or Afro-Brazilian influence. According to his ideas, art with nationalist themes would always remain secondary, limited, and even anecdotal, in contrast to the internationalist tendency that should prevail in this century. Needless to say, the evolution of art in this century, including Brazilian art over the past twenty-five years, would demonstrate the originality of Ismael Nery’s avant-garde position—one he consistently maintained throughout his brief yet fruitful life as a painter and draftsman".

Antônio Bento

"Already in the early 1920s, we see emerging in his painting the atmosphere Di (Cavalcanti) described as ‘penumbrist’ in reference to this same period of his own work. In this first phase—what Antonio Bento referred to as ‘expressionist’—we notice that ease, redundancies, thematic reprises, and literary elements are frequent in his portraits and figures up until around 1923, suggesting a large output yet a slow evolution. However, from 1924 onward, Cubist rigor begins to structure his painting through the reduction of elements and the self-discipline that would increasingly define his oeuvre. This transitional period extended until about 1927, the time of his stay in Paris.

Chagall’s presence—and later, a metaphysical influence—emerges as another singular factor within Brazilian Modernism starting with Nery: a classicizing metaphysical tone paired, in his case, with an unprecedented exposure of self in Brazilian art. Indeed, Ismael Nery reveals himself in his works as few others do, and within this act of visual expression lies an implicit offering of his intimacy to the reflective viewer".

Aracy Amaral

"Ismael Nery possesses a vast painterly talent, though—with the exception of a few canvases—his body of work often bears an unsettling sense of incompletion. Yet he is a researcher of the noblest kind. He lives in an almost mystical obsession, preoccupied with certain plastic problems—chiefly composition with figures and the creation of an ideal human type. Viewing his works preserved in the home of Murilo Mendes, who safeguards them in Rio, one has the impression that problems are posed in some canvases, developed in others, and concluded in yet others.

His pursuit of an ideal plastic type representative of humanity links him with deeply moving European seekers—particularly Modigliani and Eugène Zak. Thus, with all his figures converging toward a single, elusive type that never fully satisfies him, Nery arranges them in every possible composition, seeking purely plastic balance and harmony. These concerns with composition and the ideal type so preoccupied him that, for a long time, he abandoned color altogether, working only in blue. This ‘blue phase’ is truly striking as a psychological phenomenon, and some works from this period seem to me among the most remarkable Brazilian Modernism has produced".

Mário de Andrade

"Ismael Nery’s inflated ego—at the intersection of mythomania and mysticism—would draw his persona ever closer to that of the Christian figure. Not only was he buried in the habit of Saint Francis, but he also sought to align his death with Good Friday, when, like Christ, he was 33 years old. He missed by a week, passing away on Easter Friday. He died mythically, surrounded by the number three—symbolically reenacting the age at which his father, also named Ismael, had died. Ismael-father and Ismael-son. The physician and the patient. Ismael-Christ and Ismael-man. The SELF and the OTHER. Two in one. Three in one: the mythical and psychoanalytic circularity of 33.

Much of what we have said so far can be revisited in his paintings and reread in a poem entitled ‘Eu’ (‘I’), written in his final year, where he begins: ‘I am the tangency of two opposing and juxtaposed forms.’ The poem unfolds as a confrontation of forces tending toward the annulment of the individual. This verse is emblematic of his initial refusal of individuality from a subjective standpoint. From an aesthetic perspective, it reflects the roots of the Cubist style he adopted. The fragmentation of figures, the two or three faces in conflict, correspond both to a stylistic gesture and to the schism within the tormented spirit of an artist seeking unity in what he called ESSENCE—an ESSENCE that did not erase the human traces, the flaws, the scars".

Affonso Romano de Sant'Anna

"It was at the end of 1921 that I first met Ismael Nery. I worked at the former Directorate of National Heritage within the Ministry of Finance. Ismael Nery had been appointed as a draftsman in the architecture and topography section. One fine day, a young, well-dressed man entered the room. He set up his drawing board, sat down, and began to work. Half an hour later, he left for coffee. Seizing the opportunity, I took a peek at what he was doing: he was sketching figures around a customs house project. When he returned, I struck up a conversation. We left the office together. Thus began a friendship that continued unbroken until his death on April 6, 1934.

Ismael had just returned from Europe, where he had spent a year refining his painting studies. I recall him speaking with enthusiasm about the exhibitions and museums he had visited, yet he did not refer to any particular painter of the time. He anticipated a major transformation in the concept of the artist—or perhaps a return to the classical ideal—for he saw the artist as a harmonious, learned, and visionary being, not merely a cultivator of temperament. He regarded painting as being in crisis, facing the rise of cinema.

Years later, I remembered these early conversations upon reading André Breton’s essay, which begins more or less like this: ‘The camera has dealt a mortal blow to the old means of expression [...]’. Ismael felt that many of painting's intentions had been definitively realized: for instance, when he first saw Tintoretto, he thought it pointless to continue painting. Thus, I first knew Ismael Nery as a painter, draftsman, and architect. But soon, other, deeper aspects of his personality were revealed to me—that of the poet, the philosopher, and even the theologian. I must say that I offer my testimony with absolute honesty, with no desire to mystify, nor any reason to agree with those who, having known Ismael Nery only superficially, deny his greatness and accuse me of trying to create a myth".