Luiz Sacilotto

Luiz Sacilotto (Santo André, SP, 1924 - São Bernardo do Campo, SP, 2003)

Luiz Sacilotto was a painter, sculptor, and draftsman. He studied painting at the Brás Professional School for Men, between 1938 and 1943, and drawing at the Brazilian Association of Fine Arts, from 1944 to 1947. His early works demonstrate a rejection of academic standards and a close affinity with the aesthetics of the Santa Helena Group. From 1944 onward, he began to develop an expressionist work that deepened until, in 1948, it reached a vigor strongly marked by intense colors and forms. In 1945, he reconnected with his colleagues from the Professional School for Men, the artists Marcelo Grassmann (1925) and Octávio Araújo (1926), who introduced him to Andreatini (1921). Together, and with the help of Carlos Scliar (1920 - 2001), they held the exhibition 4 Novíssimos, at the Brazilian Institute of Architects - IAB/RJ, in Rio de Janeiro, and became known as the Expressionist Group. Sacilotto worked at Jacob Ruchti's architectural firm around 1946. In the same year, he participated in the exhibition 19 Pintores, held at the Galeria Prestes Maia, in São Paulo. During this event, he came into contact with Waldemar Cordeiro (1925 - 1973), Lothar Charoux (1912 - 1987), with whom he later founded the Ruptura Group, alongside Geraldo de Barros (1923 - 1998), Féjer (1923 - 1989), Leopoldo Haar (1910 - 1954) and Anatol Wladyslaw (1913). Participating in the group was important for his theoretical refinement and the development of his studio work, which had been developing an abstract-constructive consciousness since mid-1948. He was one of the founders of the Associação de Artes Visuais Novas Tendências (New Trends Visual Arts Association) in 1963. He was considered one of the most important concrete artists in Brazil and, with his paintings that explore optical phenomena, one of the precursors of op art in the country.

Critical Commentary

Between 1938 and 1943, Luiz Sacilotto studied painting and decoration at the Brás Professional Men's School and earned a master's degree in painting from the Getúlio Vargas Technical School. He became friends with Marcelo Grassmann (1925) and Octávio Araújo (1926). Between 1944 and 1946, he worked at Hollerith do Brasil as a lettering designer. In mid-1946, he joined Jacob Ruchti's architectural firm as a draftsman.

In the 1940s, he produced numerous drawings, usually portraits, and began painting landscapes and still lifes. Throughout this decade, the expressionist tendency of his work became more pronounced, as can be seen in *Portrait of the Painter Octávio Araújo* (1947) and *Portrait of Helena* (1947), the latter executed with intense colors and forms. However, his contact with the work of Jacob Ruchti—who had exhibited a rigorously geometric aluminum sculpture at the 3rd Salão de Maio in 1939—and his connection with the ideas of Waldemar Cordeiro (1925–1973) led him to embrace abstractionism. From 1947 onward, a tension between the figurative and the abstract can be observed in his canvases, evident in the geometrical background, worked with straight lines and areas of color, and a greater synthesis of elements, as, for example, in *Figure or Sitting Woman* (both 1948). Sacilotto also created a series of abstract monotypes. In 1950, he definitively abandoned figuration and executed Painting I, which presents formal features similar to those of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). In 1952, he joined the Ruptura Group, alongside Waldemar Cordeiro, Geraldo de Barros (1923-1998), Féjer (1923-1989), Leopoldo Haar (1910-1954), Lothar Charoux (1912-1987), and Anatol Wladyslaw (1913).

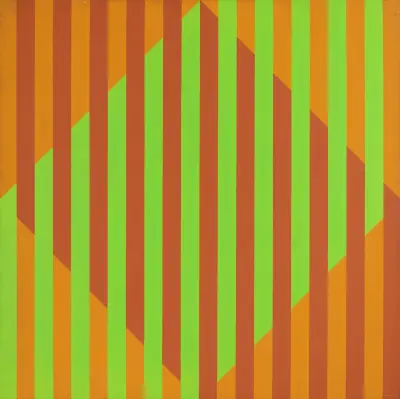

The artist, defined by Waldemar Cordeiro as "the cornerstone of concrete art," explores in his works the principle of equivalence between figure and ground, the equality of measure between solids and voids, and the contrasts between positive and negative. He uses unconventional materials such as enamel, plywood, asbestos-cement sheets (the popular name for fiber cement), aluminum, brass, and iron as raw materials and supports for his works. Beginning in 1954, Sacilotto began to title his paintings, reliefs, and sculptures Concreção (Concretion) and number them by year and sequence of execution. In Concreção 5521 (1955), he presents juxtaposed squares in white, gray, and black, intersected by parallel black and white lines. The rhythm of the work is established by the regular intervals formed by the alternation of colors and lines, based on rules of symmetry and the inversion of positive and negative. In Estruturação com Elementos Iguais (Structure with Equal Elements) (1953), he aligns small black and white squares diagonally on a blue background. The arrangement and variation of colors throughout the whole gives us a pulsating sensation. He is also a pioneer in the realm of three-dimensionality, unfolding the plane within space. In the sculpture Concretion 5730 (1957), he works on a square of aluminum: through symmetrical cuts and folds, he creates a support that allows the piece to become self-supporting, without the need for a base. Using a similar cutting and folding procedure, in Concretion 5942 (1959), he alternates solid and empty spaces to create multiple planes.

Sacilotto regularly divides the figures to multiply them, without losing the initial reference, and creates an ambiguous play with forms, working with issues that would later be developed by Op Art. In the various series produced since the 1970s, he produces effects of expansion and contraction, rotations and virtual folds, achieving great dynamism based on elementary forms. In Concretion 7553 (1975), for example, the modules are expanded or contracted to create visual volumes, generating illusions of curve and depth.

In his compositions, colors highlight or soften the geometry. The artist, who takes special care with these, collects pigments, classifies, and numbers gradations, which reach over 300 tones and range from Sienna and Kassel earths to blues and greens from Minas Gerais deposits.

In 2000, as a tribute from the city hall of Santo André, the artist's hometown, the city's main commercial street, Coronel Oliveira Lima Street, was paved with tiles reproducing his works. Also installed at the site is the sculpture Concretion 0005, and in the IV Centennial Square, the sculpture Concretion 0011, both created that same year.

Criticism

"This artist, born in Santo André (SP), made his first abstract forays into Indian ink drawing and monotype in 1947, shortly after the 1949 exhibition. His entire, decisive, previous expressionist phase was then abruptly ended, and this interruption is an excellent example of the new and abrupt art cycle that began in the country. From 1948 to 1951, Sacilotto went through a period of pictorial experimentation with formal solutions close to Cubism and Mondrian. In 1952, he signed the Manifesto Ruptura, becoming a prominent member of the Concrete movement and aligning himself with Cordeiro. To define the spirit The constructive nature of his art, developed across a broad spectrum of materials and techniques, contributed to the experience he acquired as a technical draftsman. (...) His work, among the most stripped-down and sensitive of the entire group, immediately glimpsed the serial quality and discovered the possibilities of op vibration, as well as contained spaces—forms of Gestaltian concern. In a recent phase, he came very close to Vasarely's solutions (1908)."

Walter Zanini

ZANINI, Walter. Concrete and Neoconcrete Art in Brazil. In: ___. General History of Art in Brazil. São Paulo: Instituto Walther Moreira Salles: Fundação Djalma Guimarães, 1983. v. 2, p. 881.

"The course of Luís Sacilotto's work is unique. In projects dating from 1955, he studies regular principles that enable the transformation of the support while maintaining the constant orientation of parallel lines. The theme had already been addressed by Albers, and one of Sacilotto's solutions, the Concretion, which he numbered 5521 in 1955, achieves refined relationships between line and plane. It consists of three juxtaposed squares that define the horizontality of a rectangular support. The regularity of the squares—one white, one gray, and one black—is imposed, and they can be seen one by one. Simultaneously, the sequences of parallel lines demarcate two rectangles, permeating the squares and favoring interpenetration. The simple principles of alternation and equivalence of lines activate perception, promote new values, and suggest planar sliding. (...)

Sacilotto's acute sensitivity is consistent with the concentration of functions in regular figures and with the adoption of such basic principles as division in half. Sacilotto works with a reduced number of figures, organized according to 'simple' geometry. Permanent and synthetic relationships lend quality and strength to his work. The equivalence between figure and background, one of the basic postulates of perceptual differentiation, finds a rich repertoire in it. Sacilotto explores the Albersian theme of equivalent lines of extreme differentiation: between black and white. The effects achieved on the central vertical axis of Concretion 5521 are striking, where the equal measurement of the white, gray, and black intervals reveals a departure that would be very fruitful for the artist.

The qualitative leap occurs in the painting's cut: through the affirmation of the material support, as a concrete plane, and through the drawing, exuding the flat extension of the support. Through this resource, the positive/negative relationship will qualitatively transform into the duality between the full support intercepted by the empty space. The two-dimensional plane gains space and folds over it, in the much-vaunted noble chapter of reflection on the plane and its limits. of representation".

Ana Maria Belluzzo

BELLUZZO, Ana Maria. Rupture and Concrete Art. In: AMARAL, Aracy (coord.). Constructive Art in Brazil: Adolpho Leirner Collection. São Paulo: DBA, 1998, p. 122-124.

"Concrete transformed into a game full of pleasure and hidden sensitivity. Modules, meshes, networks, grids, progressions, mathematics, and geometry are the means by which Sacilotto weaves a result where order, clarity, and definition are expected.

But, this entire structure is subverted by optical/kinetic effects that generate unexpected movements and rhythms.

Inspired by Mondrian and Gestalt, he researches changing figure/ground effects - the force of emptiness in relation to form. He falls in love with parallel (lines) because they allow for an ambivalent reading of the full-empty, positive-negative relationship. And it is in ambivalence that the essence of pleasure lies, in the game of transgressing the calculated and, thus, going beyond the expected."

Nancy Betts

LUIZ Sacilotto: studies and drawings. Santo André, Luiz Sacilotto Art Office, 1998.

"Sacilotto's work displays extraordinary internal coherence when the supporting plane is elevated to the three-dimensional. The key to understanding this production lies in perceiving the binary principle that governs it. The alternation between light and dark, full and empty, positive and negative serves to construct both painting and sculpture. The constant application of this principle, almost a constructive method, is well exemplified in the Concreções (Concretions) of the 1950s, in which the square serves as the leitmotif of an extensive series. Of particular interest is the dynamism that Sacilotto achieves from this elementary form and the richness of variations revealed within the discipline that imposes itself. He plays with the ambiguous perception of what is in front of, behind, or between the square, whether painted, cut, or folded. The use of these possibilities foreshadows the intensive use of optical-kinetic effects characteristic of op art that would occupy the artist years later."

Maria Alice Milliet

MILLIET, Maria Alice. Constructive Tendencies and the Limits of Visual Language. In: REDISCOVERY EXHIBITION, 2000, SÃO PAULO. Modern Art. São Paulo: São Paulo Biennial Foundation: Brazil 500 Years Visual Arts Association, 2000. p. 53.

"By exploring the vast aesthetic territory of geometric abstraction, Sacilotto created indelible maps, visualities that integrate with our gaze like an alphabet. (...) Sacilotto meticulously plans and executes projective codes or translations and rotations of forms capable of subverting the viewer's gaze. Capable of seducing them to another and yet another perspective. Always emerging from these immersions with a sense of discovery provoked by a challenge: to look again and deeper.

In some of these compositions on paper, there are undoubtedly reflections of optical art, which was fundamental in the mid-1960s. It is impossible to look at works like Abstract 236 or Abstract 242 without observing the subtle understanding or expansion of modules that promote virtual volumes, sculpting illusions of depth on the flat surface of the paper, in infinite twists and extensions.

These ambiguities of perception are all the more admirable for having been created with simple instruments: a ruler and pencil. As, indeed, are the patient vanishing lines of Renaissance perspective. Light-years ahead of the era of computer graphics, Sacilotto's works are formally and poetically much denser than most of the experiments conducted with these new cybernetic instruments, whose potential remains largely unexplored in artistic creation.

Another identifiable aspect of Sacilotto's works is, in a way, kinetic art. Although the artist never envisioned mechanisms or gears to move his forms, and pur si muove (as Galileo would say), they move nonetheless. Driven by a sophisticated virtual motor, which Sacilotto installs in our retinas the very instant we stand before one of these works.

Angélica de Moraes

MORAES, Angélica. Worker of Form. In: SACILOTTO, Luíz. Drawings: 1974-1982. Text by Angélica de Moraes. São Paulo: Sylvio Nery da Fonseca Escritório de Arte, 2001.p. [5].

Interview with Nelson Aguilar

Sacilotto, the working-class knowledge of concrete art

Folha de S.Paulo (Illustrated) - 04/20/1988

In Luiz Sacilotto's studio in Santo André, a calm order reigns. In a corner of the mezzanine, there are four sculptures: three of his own work and a reproduction of Michelangelo's statue of Lorenzo de' Medici. The contemplative figure's bent arm and the triangle formed by the posture of the legs align with the right angles of the pieces by the founder of São Paulo concrete art, along with Waldemar Cordeiro. There is an impeccable coherence in the artist's attitude, something that comes from artisanal, manual knowledge. I discover another unfolding of the Florentine precursor's presence: beyond the formal aspect, there is active, practical thought. The history of Brazilian art must sharpen its analytical tools to account for this work. There's no point in viewing it from above. Sacilotto brings with him the sedimentation of working-class knowledge, an anti-elitism so cultivated that the only honest attitude for a scholar is to sharpen his listening. Note throughout the interview how he puts in their proper place the concretist controversies that graced the fashionable salons.

In the exhibition that the Millan gallery inaugurates, Expressionism is represented by a diagonal line in the 1948 "Still Life."

I had brought a figure, a portrait of Helena, my wife. In the background of the portrait there was a spatial, constructed connotation. Given the physical space of the exhibition, it was the only figure, somewhat out of place. I chose "Still Life" as a sample of a constructive beginning. During this period, Waldemar Cordeiro came to Brazil. When it was observed that there was a constructive force within our figures, an interest began to emerge in discussing the subject in more depth, in projecting, in seeing what was happening in the visual arts worldwide.

How did Waldemar Cordeiro emerge in this environment?

He was different, he stood out from the crowd. Very demanding, he didn't tolerate injustice or mistakes. He didn't let anyone take the initiative; he was always the first. He was usually right. He was studious. He had an academic background, an excellent background in art history, which we didn't have here. There was that senseless quarrel between figurative art and abstract art, which we didn't get into.

A painting like the white one from '52, with no horizon line, shapes in an infinite space, didn't cause problems at the time?

Absolutely. I was quite confident in what I was doing. These early, spatial works are also justified by my professional training. My first apprenticeship, more artisanal, from '38 to '43, was as a drawing and sculpture teacher. But it was a transition to more industrial work. My first job was as a letterer. At the time, so-called typographic fonts were poor. The drawing was done entirely by hand.

The work of a letterer already requires a degree of abstraction. That's how you distinguished yourself from your colleagues.

Right, there was rigor. When I broke out of that rigor, it was the figure, especially the woman. She was the great model. I drew and drew. One or two objects. But the human figure impressed me more: posture, gestures. Then, through colleagues, "Don't you want to work in architecture?" Of course! It had excellent possibilities, because at that time the mormograph didn't exist. Everything was drawn by hand. All the architectural work moved me enormously. The rigor, the discipline, the orthogonal drawing. New information began to arrive. My friendship with Cordeiro grew closer. Working in architecture, I had a fondness for Mondrian.

At the 1st Biennial, Max Bill, Sophie Tauber, and Arp came.

And we immediately connected because they work in a field that particularly interests us. We got in touch with two or three colleagues who had similar ideas to ours. For example, Geraldo de Barros. Or Lothar Charoux. There were painters we respected. The idea of holding an exhibition of concrete art, a term from the 1930s, Theo van Doesburg, matured. We adopted it because we felt our geometry was quite different from the Flexor group that was active in São Paulo. They had that freedom... while we followed a rigorous, modulated art. The difference with abstract art is that in this case, certain elements could be added or removed without destroying the painting. Whereas in our case, removing a small square, a red one, interrupts the circuit. It's impossible to add another square; it would destroy the order.

There was a negative repercussion in Rio when one of the members of the São Paulo group declared that the color order didn't matter; even a permutation wouldn't alter the formal order.

It wasn't a confrontation with Rio. It was a comment that was being discussed without much reason. I think other, more serious reasons should be discussed. There's so much discussion up there, and here below, we're trying to work on something else. I was a metalworker, a designer of metal frames, to be able to finance and sustain the painting. During the day, they worked in the metalwork shop and painted at night.

Aracy Amaral also observed a fundamental difference between the group from Rio and the one from São Paulo, regarding the artists' social status. In Rio, they didn't need to be professionals in other fields, as they belonged to more privileged classes.

These were people who already had a reasonable economic base. In Rio de Janeiro, they fit in as teachers or in the newspaper, something already linked to their field of work. In our case, like Ivan Serpa, Aloísio Carvão. Here we never had the opportunity to work in that field. Charoux sold thread.

Did he stay in that situation the whole time?

Until retirement. Geraldo de Barros was an employee of Banco do Brasil. Waldemar Cordeiro practiced landscaping, avant-garde gardening, but wasn't specifically a visual artist. Féjer had a small acrylic coating business. I worked at Fichet, one of Brazil's largest window and door companies. From there, I became independent for 11 years and started a metalworking business. I returned to Fichet, where I retired in 1977. It wasn't until 1978 that I had my first chance to travel to Europe.

What artists impressed you then in Europe?

In Amsterdam, Malévitch and Van Gogh. Another thing that struck me was the sheer scale. The encounter with Paolo Uccello's Battle at the Louvre left me speechless.

Returning to the Rupture Manifesto (52), it was your affirmation as an artist.

The name of the exhibition itself said it all. Rupture also meant breaking with the general situation, pseudo-art, art covered up by institutions. We were against situations within the Museum of Modern Art itself, against conformism, not only from a theoretical and pictorial perspective, but also from a social perspective. It had a huge impact.

Did you sell in Rio?

Very rare. More in São Paulo.

And in your case?

Two paintings in the Salão da Arte Moderna, at the Prestes Maia gallery. Theon Spanudis said: "When the exhibition is over, I'll buy them both."

You received recognition from Mário Pedrosa, who even did a brilliant analysis of your painting today at the MAC.

He respected me greatly. He knew how to see series, parallels, persistence.

Critically, you were well supported at the time. If there had been a correspondence at the art market level, you would have been in an advantageous position.

There was a lack of a little more knowledge on the part of general critics. The exception was Pedrosa. Critics weren't sufficiently informed.

And the dispute between concrete and neo-concrete?

There is no such confrontation. The controversy between Gullar and Cordeiro is not between us. Weissmann and us, Aloísio Carvão. A few years ago, we had a small roundtable discussion on TVE in Rio de Janeiro, where we even got together. When Aloísio Carvão travels, the news comes out: "The Neoconcrete artist is leaving for Europe tomorrow." He said, "What's this Neoconcrete business? I'm concrete!"

Reading the statements today, one gets the impression of strong antagonisms like those between Cordeiro and Fiaminghi. It wasn't ideological. It was personal resentment. Then I made the suggestion: why not try to regroup even elements that weren't part of the Ruptura group, but with which we had a certain connection? Fracaroli was somewhat Mondrianesque. I've always had excellent friendships with Willys and Barsotti. With a few other members, something cooperative was done. We rented a room that would be permanent for our gallery called Novas Tendências. The first exhibition was in '63, followed by two more. But there came a point of saturation, not artistically, but economically. It closed in '64, when things began to change politically.

At that point, how did things affect your work?

During that period, I was working at the metalwork shop. I hadn't stopped producing. But the impact was strong. Things happen that directly affect us, our colleagues. I became emotionally involved. My works that were in the Cultural Center were thrown away, taken away. I built a completely non-structural structure, a complex of scrap metal, of angle iron. I made an overturned baby stroller. I found some torn truck upholstery with coil springs in a scrap yard. This piece was exhibited at one of the Biennials. From then on, there was no longer any possibility of exhibiting. It was overly guarded.

Does a silence occur then?

I stopped producing for six or seven years, just to focus on my professional and family life. In the early 1970s, I began to review what I had done. I felt a huge need for all the elements to create more movement, not be static, so gestalt-like. I began a series of studies, a series of gouaches that triggered many works. The rotations.

Only you and Charoux from your group in the 1960s didn't return to figuration. Cordeiro does popcreto, Maurício Nogueira Lima, the soccer players, Geraldo de Barros also experiments with work with images.

I was very conscious. For me, reality was exactly what I was doing. That vision of socialist realism is an abstraction we know well, when perspective appears, all this evolution. Concretism is not an ism. Concrete art is an art of design, of programming. You can develop to infinity, almost like discovering perspective, which opens up a vast field.

And the sculptures? You work with hollow forms. The void is very important. Air is a substantial part.

The void is a component. The origin, a good portion of these sculptures, comes from my proposal: within a flat surface, through cutting and folding.

From when?

Mid-50s.

Did you work at Fichet? What's the relationship between sculpture and professional work?

After my internship in the capital with Jacob Ruchti, I worked for a few months with Villanovas Artigas. Someone in Santo André needed people. I met a colleague who was a designer at Fichet who invited me. Before going there, I worked as a set design assistant at Vera Cruz, during the "Caiçara" and "Terra Sempre Terra" productions. In my involvement with architecture, the sculptural aspect comes into play. I have the workshop materials in hand for cutting and bending, in this case a little welding. What does it mean to cut and bend a square or circular surface and take it to another dimension? In the secular concept of sculpture, there were two processes: one, the stone block, where you remove the material, and the other, clay modeling, where you add. From our perspective, there was nothing to add or take away; it was the material itself, the sheet. But I transformed it through cutting and bending. I think that was my contribution. The voids have the same effect as the full ones.

It's a different void than Henry Moore's, still an expressionist. There's no naturalistic support here.

Henry Moore is an extension of the things of nature; the figures themselves are quite organic, there's an elegance, a very great formal beauty, but it's an extension within nature. Ours isn't connected to anything; it's an object that was designed, programmed to be just that. In this case, a cube made of eight triangles that turns into a cube inside that doesn't exist.

What do you think of these Modernity-style exhibitions, which establish a Treaty of Tordesillas in Brazilian art, determining which artists are qualified to represent the country?

Naturally, we were hurt. Who wouldn't want to participate in an event abroad? But the situation was such that no one is to blame. Next time it will be the same. Sometimes it's also a bit of our own fault. There needs to be greater participation, with all our colleagues. Many people were missing. We need to create a more democratic, more comprehensive system. What didn't convince anyone were the defenses of why that was done. Even the delegation itself didn't justify itself. It was regrettable.

Collections

Picoteca Collection of the State of São Paulo/Brazil

Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection - MAM RJ

University of São Paulo Museum of Contemporary Art Collection - MAC/USP

Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art Collection - MAM/RJ

São Paulo Museum of Modern Art Collection - MAM/SP

São Paulo Municipal Art Gallery

Santo André City Hall

São Bernardo do Campo Municipal Art Gallery

Solo Exhibitions

1980 - São Paulo, SP - Sacilotto: Expressions and Concretions, at MAM/SP

1982 - São Paulo, SP - Luiz Sacilotto: Works from the Last 5 Years, at Galeria Cosme Velho

1985 - São José dos Campos, SP - Paintings, at Galeria do Sol

1986 - São Paulo, SP - Luiz Sacilotto: Paintings, at Galeria Choice

1988 - São Paulo, SP - Solo Exhibition, at Galeria Millan

1995 - São Paulo, SP - Sacilotto: Selected Works, at Escritório de Arte Sylvio Nery da Fonseca

1998 - Santo André, SP - Study at Casa do Olhar

2000 - São Paulo, SP - Luiz Sacilotto: Complete Printed Works, at Espaço de Artes Unicid

2001 - São Paulo, SP - Sacilotto: Works from the 90s, 50s, and 40s, at Dan Galeria

2001 - São Paulo, SP - Drawings 1974/1982, at Galeria Sylvio Nery

2001 - Santo André, SP - Complete Printed Works, at Paço Municipal

Group Exhibitions

1946 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Quatro Novíssimos, at IAB/RJ

1947 - Santo André SP - 1st Fine Arts Salon of Santo André - 2nd Prize

1947 - São Paulo SP - 19 Painters, at Galeria Prestes Maia

1951 - São Paulo SP - 1st São Paulo International Biennial, at Pavilhão do Trianon

1951 - São Paulo SP - 1st São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia

1952 - São Paulo SP - 2nd São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia - Governor’s Prize

1952 - São Paulo SP - Grupo Ruptura, at MAM/SP

1952 - Venice (Italy) - 26th Venice Biennale

1953 - São Paulo SP - 2nd São Paulo International Biennial, at Pavilhão dos Estados

1954 - São Paulo SP - 3rd São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia - Acquisition Prize

1955 - São Paulo SP - 3rd São Paulo International Biennial, at Pavilhão das Nações

1955 - São Paulo SP - 4th São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia

1956 - São Paulo SP - 1st National Exhibition of Concrete Art, at MAM/SP

1957 - Buenos Aires (Argentina) - Modern Art in Brazil, at Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

1957 - Lima (Peru) - Modern Art in Brazil, at Museo de Arte de Lima

1957 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - 1st National Exhibition of Concrete Art, at MAM/RJ

1957 - Rosario (Argentina) - Modern Art in Brazil, at Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes Juan B. Castagnino

1957 - Santiago (Chile) - Modern Art in Brazil, at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo

1957 - São Paulo SP - 4th São Paulo International Biennial, at Pavilhão Ciccilo Matarazzo Sobrinho

1959 - Amsterdam (Netherlands) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Barcelona (Spain) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Basel (Switzerland) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Hamburg (Germany) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Leverkusen (Germany) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1959 - London (England) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Madrid (Spain) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Milan (Italy) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Munich (Germany) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe, at Kunsthaus

1959 - Paris (France) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - Rome (Italy) - Modern Art of Brazil

1959 - São Paulo SP - 5th São Paulo International Biennial, at Pavilhão Ciccilo Matarazzo Sobrinho

1959 - São Paulo SP - Concretist Exhibition, at Galeria de Arte das Folhas

1959 - São Paulo SP - Leirner Prize for Contemporary Art, at Galeria de Arte das Folhas

1959 - Vienna (Austria) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1960 - Hamburg (Germany) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1960 - Lisbon (Portugal) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1960 - Madrid (Spain) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1960 - Paris (France) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1960 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Concrete Art Exhibition, at MAM/RJ

1960 - São Paulo SP - 9th São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia

1960 - São Paulo SP - Leirner Prize for Contemporary Art, at Galeria de Arte das Folhas

1960 - Utrecht (Netherlands) - First Collective Exhibition of Brazilian Artists in Europe

1960 - Zurich (Switzerland) - Konkrete Kunst, at Helmhaus

1961 - São Paulo SP - 10th São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia - Governor’s Prize in Sculpture

1961 - São Paulo SP - 6th São Paulo International Biennial, at Pavilhão Ciccilo Matarazzo Sobrinho

1963 - São Paulo SP - Galeria Novas Tendências: inaugural group exhibition, at Associação de Artes Visuais Novas Tendências

1965 - São Paulo SP - 8th São Paulo International Biennial, at Fundação Bienal

1965 - São Paulo SP - Propostas 65, at MAB/Faap

1966 - São Paulo SP - 15th São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at Galeria Prestes Maia

1968 - Santo André SP - 1st Contemporary Art Salon of Santo André, at Paço Municipal - special room

1968 - São Paulo SP - 17th São Paulo Salon of Modern Art

1968 - São Paulo SP - 19 Painters, at Tema Galeria de Arte

1969 - Santo André SP - 2nd Contemporary Art Salon of Santo André, at Paço Municipal

1975 - São Paulo SP - 6th São Paulo Salon of Contemporary Art, at Fundação Bienal

1976 - São Paulo SP - Drawing of the 1940s, at Pinacoteca do Estado

1977 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Brazilian Constructive Project in Art: 1950-1962, at MAM/RJ

1977 - São Paulo SP - The Groups: the 1940s, at Museu Lasar Segall

1977 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Constructive Project in Art: 1950-1962, at Pinacoteca do Estado

1978 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - 3rd Arte Agora: Latin America, Sensitive Geometry, at MAM/RJ

1978 - São Paulo SP - 19 Painters, at MAM/SP

1978 - São Paulo SP - The Biennials and Abstraction: the 1950s, at Museu Lasar Segall

1979 - São Paulo SP - 11th Panorama of Brazilian Contemporary Art, at MAM/SP

1979 - São Paulo SP - 11th Panorama of Brazilian Contemporary Art, at MAM/SP

1979 - São Paulo SP - Theon Spanudis Collection, at MAC/USP

1979 - São Paulo SP - Drawings of the 1940s: homage to Sérgio Milliet, at Biblioteca Municipal Mário de Andrade

1979 - São Paulo SP - Drawing as Instrument, at Pinacoteca do Estado

1980 - São Paulo SP - Brazil-Italy Exhibition, at Masp

1980 - Tokuyama (Japan) - ABC Artists

1982 - São Paulo SP - Expressive Geometrism, at Masp

1982 - São Paulo SP - From Modernism to the Biennial, at MAM/SP

1983 - São Paulo SP - 14th Panorama of Brazilian Contemporary Art, at MAM/SP

1984 - São Paulo SP - Tradition and Rupture: a synthesis of Brazilian art and culture, at Fundação Bienal

1984 - São Paulo SP - Geometry Today, at Galeria Paulo Figueiredo

1984 - Belo Horizonte MG - Geometry Today, at Museu de Arte da Pampulha

1986 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Seven Decades of Italian Presence in Brazilian Art, at Paço Imperial

1986 - São Paulo SP - 17th Panorama of Brazilian Contemporary Art, at MAM/SP

1986 - São Paulo SP - 4th São Paulo Salon of Contemporary Art, at Fundação Bienal - special room

1987 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - 1st Geometric Abstraction: Concretism and Neo-Concretism, at Fundação Nacional de Arte. Centro de Artes

1987 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Geometric and Informal Abstractionism: aspects of the Brazilian avant-garde of the 1950s, at Funarte

1987 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - To the Collector: homage to Gilberto Chateaubriand, at MAM/RJ

1987 - São Paulo SP - 18 Contemporaries, at Dan Galeria

1987 - São Paulo SP - 1st Geometric Abstraction: Concretism and Neo-Concretism, at MAB/Faap

1987 - São Paulo SP - The Fabric of Taste: a new perspective on the everyday, at Fundação Bienal

1987 - São Paulo SP - The Craft of Art: painting, at Sesc

1988 - São Paulo SP - MAC 25 Years: highlights from the initial collection, at MAC/USP

1989 - Santo André SP - 17th Contemporary Art Salon of Santo André, at Paço Municipal

1989 - São Bernardo do Campo SP - Visions from the Edge of the Field, at Marusan Art Gallery

1990 - Brasília DF - 9th Brazil-Japan Contemporary Art Exhibition

1990 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - 9th Brazil-Japan Contemporary Art Exhibition

1990 - São Paulo SP - Figuration/Abstractionism. The Red in Brazilian Painting, at Itaú Cultural

1990 - São Paulo SP - 9th Brazil-Japan Contemporary Art Exhibition, at Fundação Brasil-Japão

1990 - Tokyo (Japan) - 9th Brazil-Japan Contemporary Art Exhibition

1990 - Atami (Japan) - 9th Brazil-Japan Contemporary Art Exhibition

1990 - Sapporo (Japan) - 9th Brazil-Japan Contemporary Art Exhibition

1991 - São Paulo SP - 21st São Paulo International Biennial, at Fundação Bienal

1991 - São Paulo SP - Geometric and Informal Abstraction: aspects of the Brazilian avant-garde of the 1950s, at Pinacoteca do Estado

1991 - São Paulo SP - Constructivism: poster art 40/50/60, at MAC/USP

1991 - São Paulo SP - Synchronies

1991 - São Paulo SP, Rio de Janeiro RJ, Bahia, and Salerno (Italy) - Synchronies

1992 - São Paulo SP - Sergio’s View on Brazilian Art: drawings and paintings, at Biblioteca Municipal Mário de Andrade

1992 - Zurich (Switzerland) - Brasilien: discovery and self-discovery, at Kunsthaus Zürich

1993 - São Paulo SP - 100 Masterpieces from the Mário de Andrade Collection: painting and sculpture, at IEB/USP

1994 - São Paulo SP - Brazil 20th Century Biennial, at Fundação Bienal

1996 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Constructive Trends in the MAC/USP Collection: construction, measurement, and proportion, at CCBB

1996 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Art: 50 Years in the MAC/USP Collection: 1920-1970, at MAC/USP

1996 - São Paulo SP - Desexp(l)os(ign)ição, at Casa das Rosas

1997 - Porto Alegre RS - 1st Mercosur Visual Arts Biennial, at Aplub; Casa de Cultura Mário Quintana; DC Navegantes; Edel; Usina do Gasômetro; Institute of Arts UFRGS; Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul; Margs; Espaço Ulbra; Museu de Comunicação Social; UFRGS Rectorate; Theatro São Pedro

1997 - Porto Alegre RS - Constructive Approach and Design, at Espaço Cultural ULBRA

1998 - Santo André SP - 26th Contemporary Art Salon of Santo André, at Paço Municipal - special room

1998 - São Paulo SP - Constructive Art in Brazil: Adolpho Leirner Collection, at MAM/SP

1998 - São Paulo SP - The Modern and the Contemporary in Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection - MAM/RJ, at Masp

1999 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Constructive Art in Brazil: Adolpho Leirner Collection, at MAM/RJ

1999 - São Paulo SP - The 1950s and Its Entanglements, at Jo Slaviero Art Gallery

2000 - Lisbon (Portugal) - 20th Century: Art from Brazil, at Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão

2000 - São Paulo SP - Brazil + 500 Rediscovery Exhibition. Modern Art, at Fundação Bienal

2000 - Valencia (Spain) - From Anthropophagy to Brasília: Brazil 1920-1950, at IVAM. Centre Julio González

2001 - New York (United States) - Brazil: Body and Soul, at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

2001 - São Paulo SP - Art Today, at Arvani Arte

2001 - São Paulo SP - Trajectory of Light in Brazilian Art, at Itaú Cultural

2002 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Paths of the Contemporary 1952-2002, at Paço Imperial

2002 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Parallels: Brazilian Art of the Second Half of the 20th Century in Context, Cisneros Collection, at MAM/RJ

2002 - São Paulo SP - 28 (+) Painting, at Espaço Virgílio

2002 - São Paulo SP - Contemporary Artists: ABCA 2000/2001 Award, at CCBB

2002 - São Paulo SP - From Anthropophagy to Brasília: Brazil 1920-1950, at MAB/Faap

2002 - São Paulo SP - Geometric and Kinetic, at Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud

2002 - São Paulo SP - Grupo Ruptura: revisiting the inaugural exhibition, at Centro Universitário Maria Antonia

2002 - São Paulo SP - Metropolis Collection, at Pinacoteca do Estado

2002 - São Paulo SP - Parallels: Brazilian Art of the Second Half of the 20th Century in Context, Cisneros Collection, at MAM/SP

2003 - São Paulo SP - Art & Artists: exhibition of nineteen painters, at Masp. Galeria Prestes Maia

2003 - São Paulo SP - Constructivism and Form as Clothing, at MAM/SP

Posthumous Exhibitions

2003 - Mexico City (Mexico) - Cuasi Corpus: Concrete and Neo-Concrete Art from Brazil: a selection from the collection of the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art and the Adolpho Leirner Collection, at Museo Rufino Tamayo

2003 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Order x Liberty, at MAM/RJ

2003 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Brazilianart Project, at Almacén Galeria de Arte

2003 - São Paulo SP - Art and Society: a Controversial Relationship, at Itaú Cultural

2003 - São Paulo SP - Artknowledge: 70 Years of USP, at MAC/USP

2003 - São Paulo SP - Paper and Three-Dimensional, at Arvani Arte

2004 - Madrid (Spain) - Arco/2004, at Parque Ferial Juan Carlos I

2004 - São Paulo SP - Metrópolis Collection of Contemporary Art, at Espaço Cultural CPFL

2004 - São Paulo SP - Constructives and Kinetics, at Galeria Berenice Arvani

2004 - São Paulo SP - Plataforma São Paulo 450 Years, at MAC/USP

2004 - São Caetano do Sul SP - Complete Engraved Work, at Fundação Pró-Memória

2004 - Tokyo (Japan) - Brazil: Body Nostalgia, at Museum of Art

2004 - Houston (USA) - Inverted Utopias: The Avant-Garde in Latin America, 1920-1970, at Museum of Fine Arts

2005 - São Paulo SP - Trajectory, Trajectories, at Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud

2005 - São Paulo SP - 100 Years of the Pinacoteca: Formation of a Collection, at Sesi Art Gallery

2005 - São Paulo SP - 10 Years of a New MAM; Anthology of the Collection, at MAM/SP

2005 - São Paulo SP - Art in Metropolis, at Instituto Tomie Othake

2005 - São Paulo SP - Visualities/Techniques, at Instituto Cervantes

2005 - Porto Alegre RS - 5th Mercosur Biennial, at Núcleo Histórico

2005 - São Paulo SP - Homo Ludens, at Itaú Cultural

2005 - São Paulo SP - Theon Spanudis Collection, at Centro Universitário Maria Antonia

2005 - Belo Horizonte MG - 40/80: an Exhibition of Brazilian Art, at Léo Bahia Arte Contemporânea

2006 - São Paulo SP - At the Same Time Our Time, at MAM/SP

2006 - São Paulo SP - A Century of Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, at Pinacoteca do Estado

2006 - São Paulo SP - Brushstrokes - Painting and Method, at Instituto Tomie Othake