Miriam Inêz da Silva

Miriam Inêz da Silva (Trindade, Goiás, 1948 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 1996)

Miriam Inêz da Silva was a painter whose artistic trajectory was marked by ruptures and tensions that lend greater interest and sophistication to her work. Born in Trindade, Goiás, she attended the Goiana School of Visual Arts before moving to Rio de Janeiro, where, between 1962 and 1963, she attended the Painting course taught by Ivan Serpa at the Museum of Modern Art (MAM). Her work straddles the popular culture of the Brazilian countryside—with references to religious festivals, oral myths, ex-votos, and children's festivities—and the urban and metropolitan environment, influenced by the mass culture of music, theater, film, and comic books.

She began her career as an engraver, quickly gaining recognition in the institutional circuit. She participated in the São Paulo Biennial in 1963 (VII Biennial) and 1967 (IX Biennial), as well as in the 1st and 2nd Exhibition of Young National Engraving at the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC-USP). After this beginning linked to popular culture and the nocturnal world of printmaking, she began to dedicate herself to painting, associated with a sunnier atmosphere.

The woodcuts produced by Miriam in the 1960s stood out for their technical quality, the rigor of the carving, and the organic adaptation of forms to the materiality of the wood. Everyday subjects—such as a dog, a car, a woman at the door of a house, a boat, or images of saints—composed a somber universe, in which the predominance of black with small white veins created a play of tension between pause and movement. The influence of Expressionism, the striking lines, and the control of light evoked the work of Oswaldo Goeldi. From the beginning of her career, Miriam established a visual conflict by giving a nocturnal expression to illuminated everyday scenes.

The artist abandoned woodcuts in the late 1960s and, in 1970, held her first painting exhibition at Loja Residência, in Rio de Janeiro. Just as she was an award-winning engraver, her performance as a painter was also remarkable, so much so that in 1983, a prolific moment in her production, she had an exhibition at the Bonino Gallery in Rio de Janeiro.

An article in the newspaper O Popular, from Goiânia, on December 20, 1983, affirmed her prominence on the national scene and transcribed the artist's opinions: "For me, painting is life. I paint what I love and feel in my heart. The people, Brazil, are a huge attraction for me. I enjoy listening to stories, popular music, and most importantly, I spend a lot of time with people, but no matter their social status. My painting owes a lot to the great masters I had in Goiás. And in Rio, Ivan Serpa."

This statement highlights the themes addressed in Miriam's painting (and engravings): aspects of sociability in rural and urban environments, popular culture, mass culture, and religious and mythical representations. The artist returns to what is alive, festive, vibrant, and everyday. Her work reveals a concern with a certain Brazilianness, found in nature and culture. In her paintings, these two aspects are represented by vegetation, the sea, circuses, parties, and children's games.

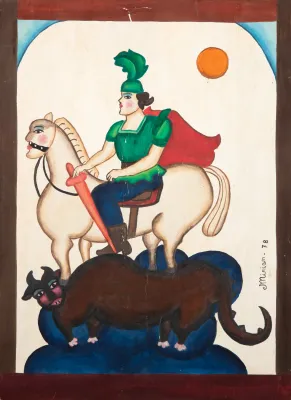

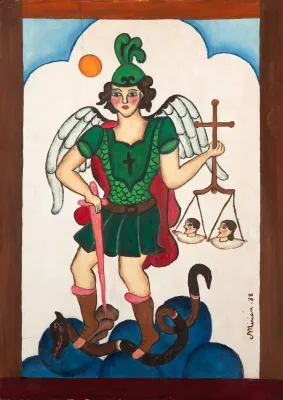

By moving from printmaking to painting, Miriam reclaimed sunlight, hidden in the darkness of her woodcuts. In her paintings with white backgrounds, the small, round, orange shape of the sun insists on appearing frequently. There is even a painting in which, on the left side, there is a crescent moon and, on the opposite right, a luminous sun.

Miriam's paintings are presented in simple, repetitive compositions on cut wood, a legacy of woodcuts. However, this apparent simplicity deserves analysis from an internal perspective. As if the tensions already noted, both in the artist's trajectory and language, were not enough, new conflicts can be seen, hidden in the apparently calm surface of her paintings.

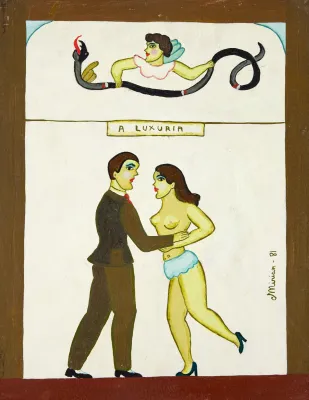

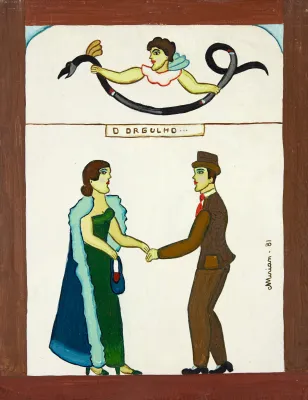

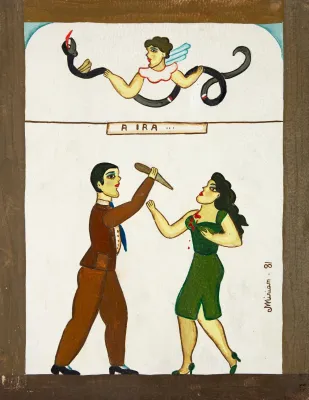

Immediately, a tension that is constantly present in Miriam's paintings stands out: the coexistence between an abstract, geometric order and a figurative order. All of the artist's paintings feature a geometric structure at the edges of the frame (bottom, top, and sides) and ample white space available for narrative in the center. Thus, her works are constituted by two pictorial orders, two visual territories, which exist side by side: the geometric abstraction of the edges and the white space for figurative elaboration.

In this sense, Miriam is more than a figurative artist, and it is appropriate to emphasize her sensitive geometric practice, close to concrete art. By visually observing the presence of these two simultaneous orders, these two movements of forms and colors, one realizes that they complement each other and also distance themselves from each other, negating each other. As a spatial composition, one part requires the other; as a discussion of language, each poses specific and differentiated problematizations. In Miriam's paintings, this conflict is not resolved, but becomes a fundamental element for understanding the particularity and aesthetic sophistication of her works.

The four bands (which can unfold into others) are free of representation, meaning in and of themselves, even though they may refer to the idea of windows, curtains, or frames. There are some paintings with curtains resting against the bands, differentiating one from the other. Therefore, the bands are neither equivalents nor representations; they are autonomous and permanent forms that imprint a specific structure on the painting, composing its totality.

As a great colorist, the artist applies different color treatments to these two aesthetic orders. The bands are rendered in dark colors and muted tones, while the forms/figurations of the white plane have light, vibrant, and bright colors. Furthermore, the bands attract and retain the light of the colors, while the forms/figures of the white plane emit and expel light. Miriam is dealing with two distinct and opposing spheres that conflictingly structure her paintings.

For comparison purposes, the color palette of the geometric stripes recalls Iberê Camargo, while the colors used to develop the figurative plane—where bright colors contrast with the background—recall Anita Malfatti and Tarsila do Amaral. Furthermore, Miriam seems to borrow from Tarsila the volumes and curved, synthetic lines used to compose her vegetation, hills, clouds, and ocean waves.

When the narrative in the white space takes place outdoors, the artist places two small blue semicircles in the upper corners of the painting, symbolizing the sky. Thus, some compositions resemble a niche or Byzantine architecture that welcomes the characters in the narrative, creating an atmosphere of spirituality.

The use of bands can be thought of as a constructive effort to compose the paintings, emphasizing the plane and the absence of perspective. Both the bands and the figurations are located on the same pictorial plane; they are created with control and with a precise definition of boundaries between forms and colors. Therefore, without the presence of a vanishing point, the images (drawn with apparent simplicity) are generally frontal, as are the bands.

The specificity of Miriam's language moves in a constructive direction. Thus, one can affirm the existence of a hybrid unity, a coexistence between different elements, imbuing her work with a particularity. The geometric dimension can be reinforced by observing that a large portion of the artist's paintings are made up of overlapping horizontal spaces.

Confronted by the immobility of the stripes and the white background, in the scenes created by Miriam, the characters are always in action. The artist captures a moment of dynamic events: outings, parties, courtships, religious ceremonies, dances, bar tables, and various performances. There is a certain tragic aspect in the observation that the fleeting, transient, changeable movement of the figurative dimension occurs alongside an inflexible, rigid, and permanent world of the geometric dimension.

In society and in the structure of Miriam's painting, there are agonizing, irreducible conflicts. Perhaps one could think that her paintings express more than just the joy of living or the celebration of life. Why not consider, from a tragic perspective, that the artist elaborates her transparent, hollow, and floating figuration as a desire for a full life, in the realization or suspicion that strong and permanent structures can be obstacles or limits to the smooth flow of everyday life?

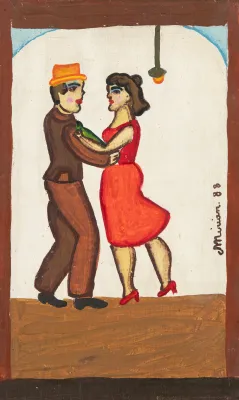

Miriam's work is permeated by several paradoxes. One of them centers on the "woman in the red dress." Just as her series of religious paintings is numerous, the question of the feminine is also noteworthy. The artist often intersects the themes of religiosity and sensuality, as seen in the paintings depicting Adam and Eve, nude and sensual, as shown in "Adam and Eve" (1992). Or she insists on the theme of couples meeting ("Gabriela and Nassif" [1978] and "Couple" [1995]).

This question becomes powerful when Miriam presents the woman in the red dress, conspicuously present in scenes of bars, dances, and celebrations. Consider the painting "Geni and the Zeppelin Man" (1981), in which the woman in the red dress poses in a determined and proud position, defiant and ready to confront man and machine.

The connection between Miriam's works and theater can be reinforced by observing that the faces of the figures painted by the artist resemble theatrical masks. Humans and animals wear a frozen and repetitive mask, with heavy makeup, rosy cheeks, and prominent lips. Her paintings present the world unfolding on a stage. The figurative action given in the white, luminous space is not real, but rather a possible representation. The mood is dreamlike, floating, and playful—everything is desire seeking visual expression.

Based on the conflict between abstract geometric order and figurative order, Miriam's work can be understood as an intermediate dimension for considering art and life. Her paintings allow us to problematize language in art and, simultaneously, convey an observer's perspective on people's lives and Brazilian society.