Victor Brecheret

The Indian And His Own Para - Marajoara Series

bronze sculpture1951

22 x 26 x 12 cm

signed on the piece

Biennial of São Paulo Award.

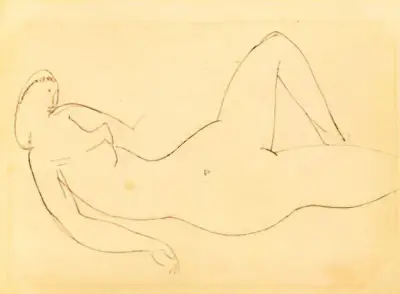

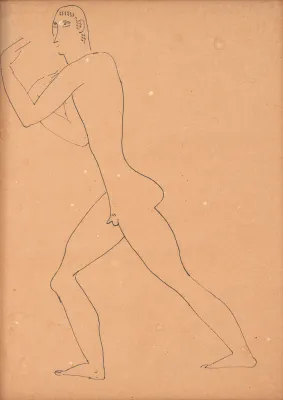

Couple

pencil and sepia drawing on paper30 x 22 cm

signed lower right

On the back of the drawing of "male figure"

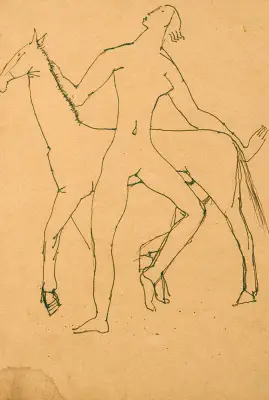

Female Figure With Horse

india ink on paper32 x 21 cm

Certificate of the Brecheret Institute. Former Paulo Figueredo Collection.

Victor Brecheret (São Paulo, SP, 1894 - idem, 1955)

Victor Brecheret was a sculptor born Vittorio Breheret in a small town near Rome. He was a prominent sculptor in Brazil. The son of Augusto Breheret and Paolina Nanni, the latter of whom died when he was only six years old, Victor was taken in by the family of his maternal uncle, Enrico Nanni. Together with his family, he emigrated to Brazil while still a child. As an adult, in his thirties, he formalized his Brazilian nationality, belatedly registering his birth in the Civil Registry of Jardim América, São Paulo. This type of registration was common among Italian immigrants in Brazil in the early 20th century.

Brecheret's artistic training began in 1912, when he studied drawing, modeling, and woodcarving at the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios de São Paulo. Between 1913 and 1919, he traveled to Rome, where he studied with the sculptor Arturo Dazzi. After returning to São Paulo, he set up a studio in the Palácio das Indústrias, where his work was discovered by the modernists Di Cavalcanti, Hélios Seelinger, Menotti del Picchia, Mário de Andrade, and Oswald de Andrade. In 1921, with a scholarship, he traveled to Paris, where he encountered renowned sculptors such as Henry Moore, Emile Antoine Bourdelle, Aristide Maillol, and Constantin Brancusi. During this period, he alternated his residence between France and Brazil until 1936.

Brecheret was a prominent presence at important international exhibitions, including the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants. Even though he was outside Brazil, he participated with 12 sculptures in the 1922 Modern Art Week. In 1932, he became a founding member of the Sociedade Pró-Arte Moderna (Spam). In 1936, he began construction on the Monumento às Bandeiras (Monument to the Bandeiras), a 1920 project that was inaugurated in 1953 in Praça Armando Salles de Oliveira in São Paulo. In the 1940s and 1950s, he created numerous sculptures for public spaces, facades, and bas-reliefs, as well as works depicting Brazilian indigenous culture in materials such as terracotta, bronze, and stone, establishing himself as one of Brazil's leading sculptors.

Critical Commentary

Brecheret began his artistic training in 1912 at the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios in São Paulo, where he studied drawing, modeling, and wood carving. In 1913, he traveled to Rome and became a pupil of Arturo Dazzi, a sculptor renowned for his monumental figures executed with great formal synthesis. In Rome, he closely studied the works of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) and Emile Antoine Bourdelle, among others, and met the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic (1883-1962). When he returned to São Paulo in 1919, he was a sculptor with broad technical mastery. He set up an improvised studio in a space provided by the engineer Ramos de Azevedo at the Palácio das Indústrias. His works were admired by a circle of intellectuals associated with the modernist movement: Oswald de Andrade, Menotti del Picchia, and Mário de Andrade.

The sculptures Ídolo and Eva (both 1919) exhibit a naturalistic treatment of anatomy and a restrained dramatic tension, expressed through body torsions and volumes shaped by strong light and shadow. The writer and critic Mário de Andrade referred to this period in Brecheret’s work (in contrast to his later Parisian phase) as the “shadow phase,” in which shadows are always emphasized over light. In 1920, he created the maquette for the Monumento às Bandeiras, evoking the bandeirantes’ quest to conquer new lands. The following year, he received a scholarship from the Pensionato Artístico do Estado de São Paulo and traveled to Paris, where he remained until 1935. Despite his absence, some of his works were exhibited at the Semana de Arte Moderna of 1922.

In Paris, Brecheret was particularly receptive to three influences that he sought to synthesize in a personal manner: the emphasis on geometric volume in Cubist sculpture, the synthetic treatment of form by the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi, and the elegant stylization of Art Deco. The convergence of these elements is evident in Tocadora de Guitarra (1923). During this phase, the sculptor reduced the dramatic intensity of his earlier works, producing simplified forms with a strong ornamental character. The sculpture Mise au Tombeau [The Entombment], 1923—now at Cemitério da Consolação in São Paulo—is one of the most notable works of his French period. It is organized in linear forms and possesses a melodic softness. The theme is treated with formal simplification, evoking a profound sense of serenity.

In 1936, Victor Brecheret settled in São Paulo, receiving commissions for public sculptures as well as religious-themed works. He resumed the Monumento às Bandeiras project, completed only in 1953. The work stands out for its figures executed with great formal synthesis, attention to volumes, simplified details, and stylized lines. The monument successfully conveys both the narrative and allegorical essence of its subject: its composition combines strong horizontal alignment with a sweeping movement that culminates in the figure of Glory, heroically uniting the entire sculptural group. The surface treatment is rougher compared to earlier works, as the sculptor emphasizes the material itself.

From the 1940s onward, the artist engaged with themes related to indigenous culture, creating sculptures in bronze or terracotta such as Drama Marajoara (1951) and Drama Amazônico (1955). At the peak of his career, he also worked with circular stones, making subtle incisions in the surfaces, as seen in Luta da Onça and Índia e o Peixe (both 1947/1948). In these works, he evokes the sacred or magical character of stones, revisiting indigenous forms and archetypes in a highly personal way, while also reflecting influences from Henry Moore and Hans Arp (1886-1966). In works such as Luta dos Índios Kalapalos (1951), he produced forms that engage with abstraction. In Índio e Suassuapara (1951), the artist starts with two volumes that merge and explores both empty and filled surfaces, incorporating incisions into the composition.

Critiques

"The only appropriate response to such works is a devout silence, a reverent silence that conveys the tacit acknowledgment that we are in the presence of something that transcends our usual perceptions. This state of mind is always reproduced (in those who possess a soul, naturally) through music, when it is Beethoven who penetrates the very essence of our being; through painting, when it manifests the hand of a genius; through verse, when sung by the supreme poets; through sculpture, when one of those rare shapers of marble breathes life into stone. Well then: if Eva by Brecheret evokes such a state of mind, nothing more need be said. It consecrates. It consecrates. And it shames our presumptuous Carthage, this São Paulo that rejects such an artist, exiles him, starves him, only to later hand hundreds of thousands to a mediocre genius in exchange for a stone-and-bronze nativity scene full of lions, panthers, indigenous figures, Trojan horses, giraffes, crocodiles, etc. Monumentally false, having forgotten the paying camels, crowned by the omnipotent, omnipresent, all-knowing, all-conquering crowbar."

Monteiro Lobato"But for me, Brecheret possesses more than the fleeting brilliance of youth. In the extended engagement during which I observed and admired him, a profound conviction took root in my spirit: the young sculptor is a distinctive personality, the most brilliant prophetic talent Brazilian sculpture has seen to date. What he lacks is a more measured contemplation of the great works of art of our time and a temperament inclined toward aesthetic reasoning, to produce the fully realized masterpiece that Brazil has yet to contribute to the international art market, and from which the world eagerly awaits."

Mario de Andrade"Anyone examining his complex evolution cannot fail to notice the increasingly pronounced focus on volumes and planes, accompanied by a growing disinterest in subject matter, theme, or figurative concession. The current phase of his stone works rigorously emphasizes this love of form for its own sake, though Brecheret masks it with somewhat convoluted explanations in his catalog. In reality, the use of natural chance and the graphic quality of primitive engravings reveal only the artist’s timidity, seeking justification for future gestures. These gestures, I believe, will involve shaping the stone itself, exploring new rhythms, ideal proportions of planes and volumes detached from the human form, emerging solely from the artist’s imagination and sensibility. From the very beginning, his trajectory is discernible to a discerning eye—in stylizations, simplifications, distortions, and syntheses. The sculptor never clung to analytical conception; when he focused on detail, it was always to make the part a whole, to value it plastically as an artwork in itself, not to assert a naturalistic tendency. And when the focus was on the whole, the detail mattered only as a solution of balance or sensitive graphic design."

Sérgio Milliet"He polarizes, like Anita Malfatti, the ideals of the modernists prior to the 1922 Week of Modern Art. His Italian training between 1913 and 1916 with Arturo Dazzi was also marked by the secessionist sculpture of the Yugoslav Ivan Mestrovic. Returning to São Paulo between 1919 and 1921, he became a renewing force, with sculptures stylized by elongations and dramatic anatomical tension. Between 1921 and 1936, his sculptural production aligns with the School of Paris, undergoing purification and simplification inspired by Brancusi and the refined geometrism of Art Deco, achieving a synthesis of abstracted volumes of great luminosity. In the 1930s, after some abstract experiments, he pursued the globalisation of forms, rustic turning, archaic simplifications, and volume cut into planes. In 1936, with the opportunity to realize the Monumento às Bandeiras, he returned definitively to São Paulo. After brief research into archaic Greek sculpture and abandoning geometrism, his mass sculptures express greater naturalism, centered on monumental female figures with Maillol-esque resonance. By the late 1940s, he focused on national, indigenous themes—his plastic language became increasingly organic, with outcroppings of profound intuition, mapping essential, primitive forms, and sensitizing the masses through incisive gestures."

Daisy Valle Machado Peccinini de Alvarado"Until 1921, the sculptor occasionally drew upon Rodinian forms; for instance, Menotti Del Picchia's Mask from that year, closely resembling Mahler's bust, nervously modeled by the French genius a little over ten years prior. With these forms of supreme elegance and refined simplicity, Brecheret rigorously formulates a style. This initial fixation of his singularity—of his 'manner'—is of paramount importance. Not because it represents a fixed style, far from it—the sculptor’s work would undergo the most radical shifts, from stones to Marajoara, from the monumental granite à la Bourdelle of the Bandeirantes to Graças I and II inspired by Maillol, etc. But because, regardless of the phase, Brecheret never relinquishes a poetic identity, always allowing recognition of the same capacity for formal synthesis, the same unmistakable style. Victor Brecheret’s greatest merit may have been his consistent choice of the greatest masters of modern sculpture as interlocutors: Rodin, Medardo Rosso, Brancusi, Bourdelle, and Maillol. That he did not always emerge unscathed from these confrontations—the only ones capable of captivating his high sculptural profile—does not diminish the grandeur of his challenges. Among us, he was the only one able to sustain them, aware that these were precisely the confrontations sculpture demands."

Luiz Marques"Without ties to the rarefied Brazilian sculptural tradition, Brecheret must be considered, as Luiz Marques suggests, within the framework of European sculpture, with which he engages in a dialogue marking his trajectory as a versatile artist. Considering his formation and long stay abroad, a crucial question arises: to what extent can Brecheret be considered a Brazilian artist? Might he, in fact, belong more to the history of European sculpture, given that his work bears few direct connections to the art produced in Brazil at the time? Even the indigenous inspiration that punctuates his final output, seemingly responding to Mário de Andrade’s 1921 exhortation—‘Study the types of our Indians, types not devoid of beauty, stylize them, unify them into a single, original type, and thus you will have acquired your greatest quality’—can be placed, albeit belatedly, within the European avant-garde’s interest in the primitive at the century’s outset. Perhaps by addressing this question, untangling this knot, it becomes possible to reassess Brecheret and recontextualize him in Brazilian art beyond mere geographical evidence, incapable of capturing the complex elements inherent in defining any artistic work."

Annateresa Fabris"Only two sculptors participated in the 1922 Modern Art Week: W. Haaberg and Victor Brecheret, the latter with twelve works. Two years prior, in June 1920, Brecheret had already presented his design for the Monumento às Bandeiras, whose construction would only begin in 1936 and finish in 1953. In other words, when he presented the project, the Week had yet to occur, and the São Paulo art scene was unfamiliar with Cubism, Futurism, Dada, and other modernist innovations. When inaugurated, the São Paulo International Biennial—a watershed in Brazilian art—was holding its second edition. Revolutionary in 1920, highly conservative in 1953. Brecheret himself, having experimented with various styles—Egyptian hieratic, Art Deco, Cubism—had by then reached full artistic maturity in bronze works adorned with rock inscriptions (Índio and Suassuapara, 1951), and in the so-called 'stone phase,' which lasted until his death in 1955, where he appropriated granite pebbles as shaped by nature, while intervening on their surface with incisive gestures."

Frederico Morais"It is in Victor Brecheret that the representation of the sacred becomes eloquent as the language of a vast production spanning his entire life. In him, sacred art finds a way to traverse all the diverse avenues of sculptural expression, from the monumentality of some São Paulo tombs to the delicate subtlety of his terracottas, whether depicting the Virgin Mary or the Flight into Egypt, the fourteen Stations of the Cross adorning the São Paulo Hospital das Clínicas chapel, or the various representations of the Last Supper, to which the artist wisely imparts an entirely original language."

Emanoel AraújoTestimonials

"I ended up in Paris," the artist says, "shortly after World War I, a time when the art revolution was reaching its peak. What I found there was completely different from what I had learned until then. I was stunned, confused. I spent a year without working, although I frequented studios and artists. Then, drawn by the environment, I entered my modernist phase. Granite figures that only presented volume (I called them tires...). Or advanced concepts in which geometry played with form, figures executed in polished copper. (...)

What is done today," the artist continues, "abroad or here in our country was already done in Europe after 1920. At that time, they wanted to do away with a certain conventionality in art, because art was saccharine, made for bourgeois tastes. An attempt was made to transform it but could not be achieved because it achieved nothing. Outside the classical foundations It would be useless to try to create something new. Besides, in art, everything that could be achieved has already been done. In the effervescence of the modernist movement, I used to wonder: then why do those famous statues in museums, which have endured for centuries without diminishing their beauty or value, continue to be the most attractive? Nothing has been able to diminish them to this day. In 1928, there was also a veritable invasion of artists from all countries in France, bringing new, revolutionary ideas. However, they soon disappeared, like a will-o'-the-wisp, nothing more. (...)

"When did you return to the classical foundations?" I ask.

"Actually," Brecheret replies, "I never strayed from them. But, driven by the influence of the time, I followed what everyone was doing at that time. Meanwhile, I sifted through my work, advancing, or rather, retreating, until I settled on it. The experience gained during the modernist period was truly beneficial to me, as I acquired a vast knowledge of geometric lines in sculpture." (...)

But the sea is a poor supplier - adds Brecheret - and in the absence of other stones whose beauty would inspire me, I have been working in terracotta, always on the same subject, with national motifs, thus seeking a new form, a new modality, another Brazilian sculpture, legitimately ours."

Victor Brecheret

ANTONIA, Maria. Brecheret speaks of art. In: BRECHERET: 60 years of news. São Paulo: s.n., 1976. p.93-95.

Collections

Collection of the Pinacoteca of the State of São Paulo/Brazil

Inter-American Development Bank - Washington D.C. (United States)

Guilherme de Almeida House - São Paulo SP

Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo - MAC/USP - São Paulo SP

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro - MAM/RJ

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo - MAM/SP - São Paulo SP

Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation - São Paulo SP

Curitiba Cultural Foundation - PR

Maria Luiza and Oscar Americano Foundation - São Paulo SP

Brazilian House Museum - São Paulo SP

São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand Art Museum - SP

Júlio Prestes Museum - Itapetininga SP

Solo Exhibitions

1920

Santos SP - Exhibition of the model of the Monument to the Andradas

São Paulo SP - Exhibition of the first model of the Monument to the Bandeiras, at Casa Byington. Construction of the monument began in 1936 and its inauguration was in 1953

1921

São Paulo SP - Solo exhibition, at Casa Byington

1926

São Paulo SP - First solo exhibition, featuring 33 sculptures from the French period. Donates Porteuse de Parfum to the State Art Gallery

1930

São Paulo SP - Individual

1934

Rio de Janeiro RJ - Individual

1935

São Paulo SP - Individual

1948

São Paulo SP - Individual, at the Domus Gallery

1953

São Paulo SP - Individual, at the Tenreiro Gallery

Collective Exhibitions

1916

Rome (Italy) - International Exhibition of Fine Arts

Rome (Italy) - Participates in the Amatori e Cultori exhibition - with the work "Despertar" (Awakening), he receives 1st prize at the International Exhibition of Fine Arts

1919

Rome (Italy) - Mostra degli Stranieri at the Casa del Pincio

Rome (Italy) - Mostra degli Stranieri at the Casina del Pincio

1921

Paris (France) - Salon d'Automne - awarded with the sculpture "Temple of My Race"

1922

São Paulo SP - Modern Art Week, at the Municipal Theater of São Paulo

1923

Paris (France) - Exhibition of Brazilian Artists, at Maison de L´Amérique Latine

Paris (France) - Opening of Maison de L"Amérique Latina

Paris (France) - Salon d"Automne - awarded for the work Mise au Tombeau (Burial)

1924

Paris (France) - Exposition d"Art Américain-Latin, at the Musée Galliéra

Paris (France) - Salon d"Automne - exhibits Porteuse de Parfum (Perfume Bearer)

1925

Paris (France) - 18th Autumn Salon, at the Grand Palais

Paris (France) - Salon de la Société des Artistes Françaises - honorable mention

Paris (France) - Salon des Artistes Français

Rome (Italy) - International Exhibition of Rome

1926

Paris (France) - 19th Autumn Salon, at the Palais de Bois

Paris (France) - Painters and Sculptors of the École de Paris

Paris (France) - Autumn Salon

1928

Paris (France) - Salon des Indépendants

1929

Paris (France) - 40th Salon des Indépendants, at the Société des Artistes Indépendants

Paris (France) - Salon des Indépendants

1930

São Paulo SP - Exhibition of a Modernist House

1931

Rio de Janeiro RJ - Exhibition at the First Modernist House of Rio de Janeiro, on Toneleros Street

Rio de Janeiro RJ - Revolutionary Salon, at Enba

1933

São Paulo SP - 1st SPAM Modern Art Exhibition, at the Campinas Palace

1934

Rio de Janeiro RJ - 4th Pró-Arte Salon

1937

São Paulo SP - 1st May Salon, at the Esplanada Hotel in São Paulo

1938

São Paulo SP - 2nd May Salon, at the Esplanada Hotel in São Paulo

1939

São Paulo SP - 3rd May Salon, at the Itá Gallery

1941

São Paulo SP - Art Salon of the National Art Fair Industries

1945

São Paulo SP - Domus Gallery: inaugural exhibition

1950

Venice (Italy) - 25th Venice Biennale

1951

São Paulo SP - 1st International Biennial of São Paulo, at MAM/SP - national sculpture award with the work The Indian and the Suassuapara

1952

Chile - Salon of the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of Chile

Paris (France) - Salon de May

Rio de Janeiro RJ - Exhibition of Brazilian Artists, at MAM/RJ

Venice (Italy) - 26th Venice Biennale

1954

São Paulo SP - Contemporary Art: exhibition of Collection of the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo, at MAM/SP

1955

Paris (France) - Brazilian Artists

São Paulo SP - 3rd International Biennial of São Paulo, at the Pavilion of Nations